Ihedioha Emmanuel Chukwunwike (MD)

Principal Investigator, My sister’s keeper Project.

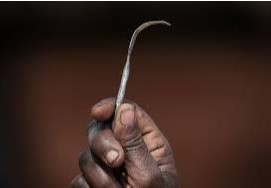

Female genital mutilation is a cultural practice that involves the partial or total removal the external genitalia of girls and young women for non-medical reasons. The practice is widespread in many cultures in Africa, Asia and the Middle East. Over the years many interventions have been implemented to end the practice, yet it continues to persist. These interventions have often focused on educating people about the harmful health effects of FGM and criminalising the practice. While these interventions have been useful, FGM still persists in many communities.

Barret, Brown and Alhassan(Barret et al, 2020) describe the REPLACE Approach- a collaborative community research program that aims, over time, to bring about changes in norms and attitudes to tackle FGM in migrant communities in Europe This community based participatory action research initiative has contributed substantially to the knowledge base that informs the role the wider socio-cultural context has on influencing individuals to perform FGM. Barret et al work is based on community-based behaviour change interventions which empower influential community members to challenge the beliefs and social norms that support the practice of FGM, including the development of a culturally appropriate measure of community’s social competence. This approach has the capability for building the capacities of FGM affected communities to overturn social norms that perpetuate the practice. Additionally, the authors observed that community-based action research is a useful methodology for collecting data in FGM intervention settings as it allows for effective community engagement to identify, educate and motivate influential community members to challenge the practice, as well as obtaining useful information on the beliefs and norms that shape the practice.

Interestingly, in their work, Barret and his colleagues have demonstrated their commitment to collaborate with community residents, practitioners, and agencies to apply research-based conceptualizations and empirical findings to building a community’s capacity to protect its girls and women from female genital mutilation. This collaborative community research program is an exemplar of the successful integration of the traditional approaches to ending female genital mutilation and the participatory action research model(Connell, Aber, & Walker, 1995; Knapp,

1995;May et al., 2002).

In this commentary, I first compare the traditional approaches to ending FGM with the participatory action research model. Next, I argue that the integration of these traditional approaches and participatory action research methods, as illustrated in the Barret et al. 2020 article, is essential to the goal of sustained and effective community prevention efforts towards ending FGM.

Bodily and Sexual Integrity Approach. The bodily and sexual integrity approach was informed by feminist writings concerning women’s sexual integrity and pleasure. According to Johansen, because Western “second wave feminists” use the clitoris as a symbol of female sexuality, the practice of FGM is seen as the antithesis of women’s sexual freedom and expression(Johansen et al, 2013).

Limitations- Interestingly, this approach contradicts with the views held by many FGM practicising communities regarding FGM’s in reducing women’s sexual pleasure. For example, in some FGM practicising communities in southeastern Nigeria, the prevailing belief is that genital cutting makes women sexually accessible. However among the communities that Barret et al worked with, the control of female sexuality is a major driver in the continuation of the FGM.

In view of this, programmatic efforts geared towards ending female genital mutilation need to be aware that many members of FGM affected communities are deeply concerned about the sexual liberalism prevalent in the western feminist narrative(Johansen et al, 2013). This was confirmed in the REPLACE project where a large number of those involved in the study perceived the bodily and sexual integrity message as a threat to their deeply held religious and cultural beliefs(Barret et al, 2020). For those women who perceive their sexual enjoyment to be “normal” and providing them a sense of intimacy, then the credibility of this approach may be questioned. It is obvious that many women in the REPLACE study stated that sexual relations caused them physical and psychological pain, a minority reported that they still enjoyed sexual intimacy with their husbands. This is in line with findings from other research conducted in the EU (Leye et al,2019, Barret et al, 2011 and Theodori et al, 2005) and highlights the contradictory nature of women’s sexual experiences and highlights the paradoxical nature of using this approach with FGM affected communities to end the practice. Because of the variance in women’s sexual experiences and the fact that these messages stem from a “Western” perspective of female sexuality and embodied experience (Brandel et al, 2010). Barrer et al found that it failed to factor in the contextual peculiarities in the FGM affected communities.

Human Rights Approach. The human rights approach to ending FGM has influenced the narrative at an international level, with the UN and western international governments framing FGM as a fundamental violation of the human rights of girls and women. This approach is based on the view that there are certain universal rights which need to be respected.

Limitations- This approach has been critiqued as being “Western centric” with some authors claiming that it propagates the “Western” liberal democratic tradition, which prioritizes individual rights rather than “community” rights(Barret et al, 2017). According to Barret et al, for most participants in the REPLACE project the human rights approach to ending FGM was problematic. Issues such as “choice” and consent were discussed at great length with many asking how FGM can be condemned as a human rights violation when male circumcision is not.

Dustin and Phillips point out that the freedom to practice one’s religion, freedom from racial discrimination, and the protection of the rights of the child are all in conflict with each other with respect to the issue of FGM (Castenada et al, 2012). Most communities involved in the REPLACE study questioned the relevance of the human rights approach to ending FGM due to its focus on individual human rights and lack of cultural relevance and sensitivity particularly with

reference to religious freedom. It was perceived that Western liberal interpretations of human rights were being imposed on them. As a result a number of respondents suggested that continuing to perform FGM could be interpreted as a means by which communities retain a sense of their “ethnic identity” particularly if they feel they are being discriminated against by the wider society due to their religious beliefs and perceived “right” to perform FGM(Barret et al, 2020).

Legislative Approach – In Nigeria, relevant laws against FGM include the 1999 constitution of the federal republic of Nigeria section 34, The Child Rights Act 2003, Section 11(B) and the violence against persons prohibition Act, 2015, section 6. Various Nigerian states including Ebonyi state have the Law Abolishing Harmful Traditional Practices Against Women and Children(2001). In the EU Member States where the REPLACE project was carried out, there are legislations which criminalises the practice of FGM, either as a specific criminal act or as an act of bodily harm or injury. This includes the UK’s Female Genital Mutilation Act (2003).

Limitations- In spite of these laws there have been few or no convictions regarding FGM practice both in Nigeria and in the UK. In Nigeria, according to 28 too many-an FGM focused NGO, 20 million women and girls have been mutilated, yet there are no convictions. It has been argued that there is a general reticence about enforcing the legislation within the UK, with Phillips arguing that the UK Female Genital Mutilation Act (2003) is simply a “symbolic piece of legislation designed to point a finger of blame at particular cultural communities than to eradicate harms to women” (Cislaghi et al, 2018). These observations foster the debate as to whether legislation acts as a deterrent or whether specific criminal law provisions, such as those in the UK, Nigeria and other countries are effective in prosecuting and punishing FGM(Merry et al, 2006). Nijboer et al argue that parents and excisors simply become more aware of the legislation and find ways to thwart it; for example, by going to other communities, states and countries with less risk of prosecution (Nijboer et al,2010). There is evidence to suggest that, because of the lack of prosecutions and jail terms, this approach has not being effective in FGM practising communities (Prochaske et al,1982). From the foregoing, although legislation alone appears ineffective in addressing FGM, it does provide an “enabling environment” for both anti-FGM campaigners and community members who have taken the decision to abandon the practice. Legislation therefore provides a structural framework within which campaigners and individuals can reject arguments that promote the continuation of FGM(Shell Duncan et al, 2011).

Participatory Action Research

A key characteristic of PAR methods is shared control over the research.

May et al. (2002) describe three types of shared control: input control (whether the study will be done and, if so, with whom and where), process control (how the knowledge will be produced), and outcome control (how the knowledge

will be used). The primary anticipated benefits of PAR in community prevention are culturally relevant and effective interventions and enhanced community capacity to solve its own problems. Community members develop knowledge, skills, and confidence to solve their own problems. Due to the lack of experimental controls in this type of research, evidence that these benefits are realized come primarily from case studies (Kloos et al., 1997; Nabors,Ramos, & Weist, 2001).

Limitations. PAR results in less definitive and interpretable data regarding program efficacy (Weissberg & Greenberg, 1998). Community members may have biases that lead to exaggerated claims of the benefits of interventions they co-constructed. Because variations in program implementation are often not assessed, and controls for factors other than the intervention that might account for outcomes are absent, one cannot conclude that observed improvements are the result of the program. PAR is not well-suited to the discovery of generalized truths about intervention effects.

SUMMARY

It is difficult to assess the efficacy of these four traditional approaches to ending FGM as it has been difficult to find studies that have evaluated their success in terms of attitudinal or behaviour change. The growing numbers of people from FGM affected communities speaking out against the practice are perhaps an indication that there has been some success, but the number of criminal court proceedings against FGM gives credence that FGM continues in many countries where it is outlawed. Similarly, awareness raising information and activities undertaken by anti-FGM campaigners reviewed were in the main classified as traditional information, education, and communication. Most focussed on the health approach with some links to bodily and sexual integrity and the twinned approaches of human rights and the law. Whilst all materials had accurate and relevant information, only a minority attempted behavioural change communication. When there was a focus on behaviour change communication, it very much emphasised the role of the individual, with little if any acknowledgement of community belief systems, and thus was unlikely to change behaviour. The PAR findings showed that there were often dichotomies in the way individuals and groups of individuals received the information disseminated by anti-FGM campaigners, with many campaigners “delivering” information rather than “listening to” and responding to the specific belief systems of the communities in which they were working.

Integration of Methods

The purpose of this comparison is not to obtain a “score” in terms of the value of each interventional approach. In view of the different focus, assumptions, strengths and weaknesses of the five approaches, It is difficult to evaluate their efficacy as few studies have documented their success in ending FGM. I am of the view that understanding and appreciating the advantages and disadvantages of each, however, can lead to more successful interventional mix in addressing FGM. Barrer et al. (2020) in the REPLACE project illustrate the successful integration of these five approaches. In this integrated model, REPLACE found that anti-FGM programmes focused on the health approach (with some links to bodily and sexual integrity) and the twinned approaches of human rights and the law should also focus on behavioural change communication. And that the behavioural change communication should combine focus on the individual as well as on the community belief. This view is informed by PAR findings which showed dichotomies in the way individuals and groups of individuals received the information disseminated by anti-FGM campaigners, with many campaigners “delivering” information rather than “listening to” and responding to the specific belief systems of the communities in which they were working. From the findings of the REPLACE team, there is a need to engage with

communities in order to develop context specific messages and strategies that target emotive and rational cognitive processes that inform attitudinal and behavioural change. This can only be done by adopting a community-based participatory action research methodology.

REFERENCES

- Barrett, H.R., Brown, K., Alhassan, Y. et al. Transforming social norms to end FGM in the EU: an evaluation of the REPLACE Approach. Reprod Health 17, 40 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0879-2

- Connell, J. P., Aber, J. L., & Walker, G. (1995). How do urban communities affect youth? Using social science research to inform the design and evaluation of comprehensive community initiatives. In J. P. Connell, A.C. Kubisch, L. B. Schorr, & C. H. Weiss (Eds.), Approaches to evaluating community initiatives: Concepts, methods and contexts (pp. 93-125). Washington, DC: The Aspen Institute

- Knapp, M. S. (1995). How shall we study comprehensive, collaborative services for children and families? Educational Researcher, 24, 5-16

- May, M. L., Bowman, G. J., Ramos, K. S., Rincones, L.,Rebollar, M. G., Rosa, M. L., Saldana, J., Sanchez, A.P., Serna, T., Viega, N., Villegas, G. S., Zamorano, M. G., & Ramos, R. N. (2002). Embracing local knowledge: Enrichment of scientific knowledge and public awareness in the environmental health along the Texas-Mexico border. Unpublished manuscript. (Available from Marylynn May, Center for Environmental and Rural Health, Texas A&M University, 4455 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-4455)

- Leye E, van Eekert N, Shamu S, Esho T, Barrett HR. Debating medicalization of FGM/C: learning from (policy) experiences across countries. Reprod Health (817). 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0817-3.

- Barrett HR, Brown K, Beecham D, Otoo-Oyortey N, Naleie Z, West Midlands European Centre. Pilot toolkit for replacing approaches to ending FGM in the EU: implementing behaviour change with Practising communities. Brussels: Coventry University; 2011.

- Theodori GL. Community and community development in resource-based areas: operational definitions rooted in an interactional perspective. Soc Nat Resour. 2005;18:661–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920590959640

- Bradshaw TK. The post-place community: contributions to the debate about the definition of community. Community Dev. 2008;39(1):5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330809489738

- Brandes U, Lerner J, Lubbers MJ, McCarty C, Molina JL, Nagel U. Recognising modes of acculturaltion in personal networks of migrants. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2010;4:4–13.

- Barrett HR. Working with African communities in the EU to end FGM: The REPLACE Approach. In: Thill M, editor. Socio-cultural and legal aspects of female genital mutilation/cutting: Transnational experiences of prevention and protection. Madrid: MAP-FGM; 2017. p. 285–90

- Castenada SF, Holscher J, Mumman MK, Salgado H, Keir KB, Foster-Fishman PG, Talavera GA. Dimensions of community and organizational readiness for change. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(2):219–26

- Cislaghi B, Heise L. Using social norm theory for health promotion in low income countries. Health Promot Int. 2018;34(3):616. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day017

- Merry SE. Human rights and gender violence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2006.

- Nijboer JF, Van der Aa NM, Buruma TM. Criminal investigations and prosecution of female genital mutilation: the French practice: crime, law enforcement and safety. Netherlands: Ministry of Justice; 2010.

- Prochaske JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: towards a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982; 19:276–88.

- Shell-Duncan B, Hernlund Y, Wander K, Moreau A. Dynamics of change in the practice of Female Genital Cutting in Senegambia: Testing predictions of social convention theory. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(8):1275–83.

- Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation. New York: The Free Press; 1995.

- Denison E, Berg R, Lewin S, Tretheim A. Effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce the prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. Oslo: Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services; 2009

Dr. Ihedioha Emmanuel Chukwunwike received his MD from the University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria and is the Principal Investigator of the My Sisters Keeper project aimed at reducing the prevalence of Female Genital Mutilation in south eastern Nigerian communities.